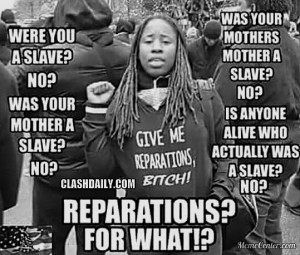

Over Easter break, I stumbled across this meme.

The meme was bad, but what really got to me was the article it was linked to, which was even worse. It started with the statement: “Blacks were treated poorly in this country for at least a couple hundred years.” My breath caught in the back of my throat. Is “treated poorly” a euphemism for enslaved-for-centuries-then-‘freed’-but-effectively-

disenfranchised-and-systematically-oppressed? “Treated poorly” doesn’t make the cut. And the questions themselves – is anyone a slave today? Absolutely yes, there are people enslaved because of their race, gender, orientation, and/or socioeconomic background. In addition, there are over two million people in the United States prison system–being imprisoned is eerily close to being enslaved.

The article ended with a complaint that since not all black people are descended from slaves and not all white people are descended from slave owners, reparation are relevant. The author clearly missed the point – not only of the woman in the meme’s shirt, but of the entire Black Lives Matter Movement, and the even greater issue of reconciliation.

Let’s get one thing straight, I am a firm believer in free speech and freedom of the press. I believe that all people need to be able to speak their minds without fear of their personal safety, but here’s the thing: if we are ever to attempt to restore relationships within our communities, then we need to speak up when hatred like this is spread around social media. When someone makes a racist joke because it is “funny” or complains about historically oppressed people groups getting angry, then I believe I am obligated to use my freedom of speech to say that it is not okay to dehumanize anyone for any reason. People are angry because they have been wronged. People are angry because they have been hurt.

You are free to say what you want, but that freedom comes with consequences – because words have consequences. Words are dangerous, thrilling, oppressive, and liberating. Just because a person has the right to say something racist (or homophobic, or classist, or transphobic, or Islamophobic for that matter…) does not mean saying it is right.

The concept of reparations is not an easy one, but is rooted in the reality of historical systematic oppression. For that reason, it must be taken seriously – particularly by those who have benefited from that oppression, and for those of you who are uncomfortable with the black woman wearing the shirt saying “Give me reparations, bitch,” it makes sense that you’re uncomfortable. No, it’s not a great way to start a dialogue, and all dialogue has to have two parties, yet I refuse to tell someone who is from a marginalized racial group the “right way” to be angry about systemic injustice. Their anger deserves to be taken seriously, even if I don’t agree with how they express it.

Over break I had the opportunity to hear Opal Tometi speak, one of the cofounders of the Black Lives Matter movement. Her presence and her message were inspirational. During the question and answer time, a young black woman stood up and asked about how she should deal with the anger she felt at injustice and oppression. Opal’s response was truly moving – that yes, there is a time and a place for anger, but when seeking systemic change we must be motivated by who and what we love rather than who or what we hate.

***

Who do you love? And how do you love them?

***

As a white woman, I don’t know from experience what it means to be a person of color in the United States. My job is not to tell others how to feel. My job is to listen to what they are saying about injustice. My job is to ally myself with them, and as an ally, to say something when I see something that is not okay.

I challenge you, the white students on this campus, to ally yourselves with those who are different from you, and speak up when you see, hear, or read something that is offensive . Who do you love? And how do you show your love? “Let us love, not in words or speech, but in action and in truth” (1 John 3:18).