The way popular forms of media create and imitate culture has always been a point of contention amongst consumers with a religious eye. Yet it elicits an unexpectedly intimate sting when you find yourself at moral odds with art that you thought came from a trusted source. For the majority of Westernized culture, Disney is a synonym for family wholesomeness. My generation was raised on the The Little Mermaid, The Lion King, and Beauty and the Beast. Now, in order to tap into the financial potential of such a nostalgic era of filmmaking, Disney is releasing live-action remakes of these stories. Part of the appeal of such projects is the effect time has in the retelling of the familiar. However, the changes are not just technical. With LGBTQ+ representation in media growing more common, Disney’s decision to embrace this change in the live-action Beauty and the Beast has left some Christians angry. There have been public calls for boycotts, open letters to Hollywood asking for revisions, and a general sentiment of “I don’t understand why they needed to change the story I grew up with by making a character gay.” While I understand this stems from a place of genuine concern, I am convicted that not only is this kind of interaction with art unhelpful, but it is not a Christian way to engage with the world.

Disney has an agenda, but that agenda is parallel to what is becoming culturally acceptable. This has never not been the case. When Andy Griffith prayed at his family’s dinner table, America generally identified as Christian, so Disney films appealed to that same sense of morality. It was the culture, and they continue to act similarly today in an environment that is less conservative. Calling it an agenda, when their platform is inspired by the climate in which they create and release content, is similar to claiming that a pastor has a religious agenda when preaching on Sundays. While it is technically true, the label means very little. Certainly anyone can come in and listen, just as anyone can go see a film, but it would be ridiculous for a non-religious visitor to hear people affirming the existence God in such a place and attempt to boycott the church. They weren’t a part of the culture of the church in the first place, even if they are invited to be. You cannot disconnect an expression from the setting in which it was conceived and created simply because it is visible to you.

Disney has an agenda, but that agenda is parallel to what is becoming culturally acceptable. This has never not been the case. When Andy Griffith prayed at his family’s dinner table, America generally identified as Christian, so Disney films appealed to that same sense of morality. It was the culture, and they continue to act similarly today in an environment that is less conservative. Calling it an agenda, when their platform is inspired by the climate in which they create and release content, is similar to claiming that a pastor has a religious agenda when preaching on Sundays. While it is technically true, the label means very little. Certainly anyone can come in and listen, just as anyone can go see a film, but it would be ridiculous for a non-religious visitor to hear people affirming the existence God in such a place and attempt to boycott the church. They weren’t a part of the culture of the church in the first place, even if they are invited to be. You cannot disconnect an expression from the setting in which it was conceived and created simply because it is visible to you.

If you decide to boycott a film based on an honest representation of humanity, then you have missed the point of sharing in creative human expression. The basis of storytelling has always been the buildup of tension created by pain and conflict, a unique product of sin, that eventually results in some sort of resolving conclusion. This means that art is inherently tainted by the reality of sin nature the same way that humanity is. So avoiding a single work based on what you perceive to be morally incompatible is counterintuitive, unless you choose to remove yourself from engaging in art as a whole.

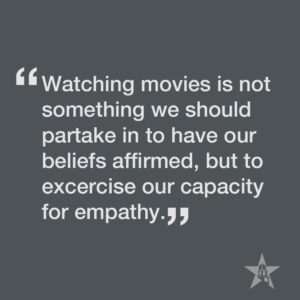

Whether or not homosexuality is a sin is not the issue. Art is meant to express the totality of the human experience and we cannot exclude an entire social group from being represented simply because their lifestyles do not align with another group’s moral convictions. Watching movies is not something we should partake in to have our beliefs affirmed, but to exercise our capacity for empathy. After all, the ability to relate to others is a muscle, something that must be trained. If we are to be like Christ then we must engage with the world the way he did, while still acknowledging the failings of humanity. This is what expression is, a way to connect and revel in the unique emotional imprints of each one of us holds within us. When we respond to popular culture as if it’s surprising that it does not live up to personal moral convictions that we all fall short of daily, then we have forgotten that.

Whether or not homosexuality is a sin is not the issue. Art is meant to express the totality of the human experience and we cannot exclude an entire social group from being represented simply because their lifestyles do not align with another group’s moral convictions. Watching movies is not something we should partake in to have our beliefs affirmed, but to exercise our capacity for empathy. After all, the ability to relate to others is a muscle, something that must be trained. If we are to be like Christ then we must engage with the world the way he did, while still acknowledging the failings of humanity. This is what expression is, a way to connect and revel in the unique emotional imprints of each one of us holds within us. When we respond to popular culture as if it’s surprising that it does not live up to personal moral convictions that we all fall short of daily, then we have forgotten that.

Everyone has the right to have stories told about them, no matter what. Don’t forget that when you go to the theater, read a book, or listen to music, that you are listening to the inner thoughts of someone’s personal expression, shared with you, not simply something to affirm you and your faith. It is a special vulnerability to experience this, treat it with care, and listen as Jesus would listen. The culture of the world will always be the world’s, and we are all a part of it. Whether or not you choose to see a film in which a gay character is portrayed positively, you are still called to interact with the world as an ambassador for Christ: with love and empathy.

Jakin is a senior communication major with a concentration in media arts and design.