“You know what Twitter needs? Less accountability. That will improve things.” This posted on Yik Yak by an anonymous poster using the pseudonym “Dean Michael Jordan.”

These days, social networks seem to be springing out of the digital woodwork. Every web developer and app designer is trying to find the niche that is as-yet untouched. Some new social networks stick around well. Others do not. Eventually, most fade in popularity, becoming replaced with others that do the same thing, only better.

Yik Yak is an app that has, so far, stuck around. For those unfamiliar with the name, allow me to explain. Yik Yak is a smartphone application that allows its users to post a short amount of text (200 characters or less), much like many other social networks. The main difference between Yik Yak and similar networks is its addition of anonymity. Those who post (“yak”) to the app are completely anonymous, their words being presented without credit given to anyone. If a user so chooses, they can adopt a pseudonym to post under. However, anyone can adopt each other’s pseudonyms or change names at any time, and so no true identity is revealed.

Yik Yak is an app that has, so far, stuck around. For those unfamiliar with the name, allow me to explain. Yik Yak is a smartphone application that allows its users to post a short amount of text (200 characters or less), much like many other social networks. The main difference between Yik Yak and similar networks is its addition of anonymity. Those who post (“yak”) to the app are completely anonymous, their words being presented without credit given to anyone. If a user so chooses, they can adopt a pseudonym to post under. However, anyone can adopt each other’s pseudonyms or change names at any time, and so no true identity is revealed.

Without any sort of identification, Yik Yak needs another way to connect its users. It chooses proximity. Users see posts from people who are using the app nearby. Readers can then vote yaks up or down, helping them reach a status of popularity, or deleting them from the feed with an overwhelming negative vote. It is also possible to reply to yaks, and to have a conversation in this way. The result for those of us who live in Houghton is a feed of thoughts, feelings, jokes, and complaints written and tailored by Houghton students, for Houghton students. And sorry for this disillusionment, but if you look through our feed, you might not like what you find.

When a given semester ends, students are afforded the opportunity to give anonymous feedback about their professors. I know I am not the only one who takes this opportunity to let out the feelings, good and bad, that I keep to myself throughout the semester. Yik Yak is a lot like these reviews. The danger comes from the pressure to write popular yaks. The Houghton feed brings up many more negative comments than I hear around campus, simply because – let’s face it – we can all agree on what we dislike about Houghton. You’ve heard it all before: the food is bad, college is hard, sleep is rare, and… people break the community covenant?

Yes, it’s true, and it’s upsetting. We have a “dark side.” I have seen posts on Yik Yak about things ranging from sexual frustration (no!), to seeking someone who will sell drugs (never!), to a recent, “Houghton, what is your favorite beer?” These are sad and, for some, shocking expressions of a group of college students who, hello, came to a Christian college. Where did they learn this evil, and why are they here?

Yes, it’s true, and it’s upsetting. We have a “dark side.” I have seen posts on Yik Yak about things ranging from sexual frustration (no!), to seeking someone who will sell drugs (never!), to a recent, “Houghton, what is your favorite beer?” These are sad and, for some, shocking expressions of a group of college students who, hello, came to a Christian college. Where did they learn this evil, and why are they here?

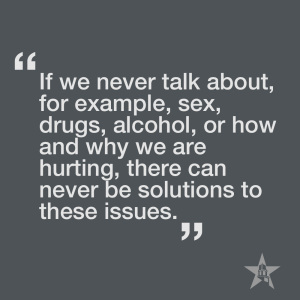

Well, at least “they” are honest about it. That might seem like a small comfort, but I mean it. These things are real, and actually happen on a regular basis. If we never talk about, for example, sex, drugs, alcohol, or how and why we are hurting, there can never be solutions to these issues. Yik Yak has created a safe space to express it all honestly. Now, let’s not confuse honesty with accuracy or authenticity. Yik Yak is NOT a perfect representation of who we are. It’s biased toward those who use smartphones, desire a place for anonymous communication, and aren’t overly frustrated with what they read. But it is entirely made up of Houghton residents. No one else is posting in the Houghton feed. They can’t.

So, then, what is the best response? Well, I’m going to keep my Yik Yak. I keep it because I don’t need to hide from mere words, especially words that give me a greater understanding of those around me, and how to love them. And I know that I am salt and light (for the Bible tells me so), so I’m going to act like it. Our feed could always use a bit more positivity and a bit more love. Of course, Yik Yak is not my mission field, and needn’t be yours, either. Most Houghton students are Christian already, and Yik Yak does not allow enough personal connection to evangelize. But I won’t be posting anything that I wouldn’t be proud to own up to. You shouldn’t either.